Introducing containers

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What are containers, and why might they be useful to me?

Objectives

Show how software depending on other software leads to configuration management problems.

Explain the notion of virtualisation in computing.

Explain the ways in which virtualisation may be useful.

Explain how containers streamline virtualisation.

Disclaimers

This looks like the Carpentries’ formatting of lessons because it is using their stylesheet (which is openly available for such purposes). However the similarity is visual-only: the lesson is not being developed by the Carpentries and has no association with the Carpentries.

Some parts of this course are in the early stages of development. Comments or ideas on how to improve the material are more than welcome!

Welcome, all

Introduce yourself and think about the following topics:

- What research area you are involved in

- Why you have come on this course and what you hope to learn

- One thing about you that may surprise people

Write a few sentences on the supplied online whiteboard.

The fundamental problem: software has dependencies that are difficult to manage

Consider Python: a widely used programming language for analysis. Many Python users install the language and tools using something such as Anaconda and give little thought to the underlying software dependencies allowing them to use libraries such as Matplotlib or Pandas on their computer. Indeed, in an ideal world none of us would need to think about fixing software dependencies, but we are far from that world. For example:

- Python 2.7 and Python 3 programs are generally incompatible

- Python 2.7 has now been deprecated but there are still many legacy programs out there

- Not all packages can be installed in the same Python environment at their most up to date versions due to conflicts in the shared dependencies

- Different versions of Python tools may give slightly different outputs and/or results

All of the above discussion is just about Python. Many people use many different tools and pieces of software during their research workflow all of which may have dependency issues. Some software may just depend on the version of the operating system you’re running or be more like Python where the languages change over time, and depend on an enormous set of software libraries written by unrelated software development teams.

What if you wanted to distribute a software tool that automated interaction between R and Python. Both of these language environments have independent version and software dependency lineages. As the number of software components such as R and Python increases, this can rapidly lead to a combinatorial explosion in the number of possible configurations, only some of which will work as intended. This situation is sometimes informally termed “dependency hell”.

The situation is often mitigated in part by factors such as:

- an acceptance of inherent software and hardware obsolesce so it’s not expected that all versions of software need to be supported forever;

- some inherent synchronisation in the reasons for making software changes (e.g., the shift from 32-bit to 64-bit software), so not all versions will be expected to interact with all other versions.

Although we have highlighted the dependency issue above, there are other, related problems that multiple versions of tools and software can cause:

- Reproducibility: we want to make sure that we (and others) can reproduce our research outputs and results. What if, a year after we have run an analysis pipeline and produced some results on a laptop, we need to run the same pipeline and reproduce the results but our old laptop has now been replaced by a new one (perhaps with a different operating system)? How can we make sure our software environment is equivalent to that on which we performed the original work?

- Workload: most people use multiple computers for their research (either simultaneously, or, over a period of time, due to upgrades or hardware failures). Installing the software and tools we need on all these systems and keeping everything up to date and in sync is a large burden of additional work we could do without. This problem may be even more severe if we have to use shared advanced computing facilities where we may not have administrator access to install software.

Thankfully there are ways to get underneath (a lot of) this mess: containers to the rescue! Containers provide a way to package up software dependencies and access to resources such as data in a uniform and portable manner that allows them to be shared and reused across many different computer resources.

Background: virtualisation in computing

When running software on a computer: if you feed in the same input, to the same computer, then the same output should appear - i.e. the result should be reproducible.

However a computer, let’s call it the “guest”, should itself be able to be simulated as running on another computer we will call the “host”. The guest computer can be said to have been virtualised: it is no longer a physical computer. Note that “virtual machine” is frequently referred to using the abbreviation “VM”.

We have avoided the software dependency issue by virtualising the lowest common factor across all software systems, which is the computer itself, beneath even the operating system software.

Omitting details and avoiding complexities…

Note that this description omits many details and avoids discussing complexities that are not particularly relevant to this introduction session, for example:

- Thinking with analogy to movies such as Inception, The Matrix, etc., can the guest computer figure out that it’s not actually a physical computer, and that it’s running as software inside a host physical computer? Yes, it probably can… but let’s not go there within this episode.

- Can you run a host as a guest itself within another host? Sometimes… but, again, we will not go there during this course.

Motivation for virtualisation

What features does virtualisation offer?

- Isolation: the VM is self-contained, so you can create and destroy it without affecting the host computer. Likewise, the software running in the VM can encounter a fatal error, crash, lock-up, etc., without affecting the host computer.

- Reproducibility: the VM can be tagged at a known-good situation. Enabling you to easily revert to this known state or share it with others, much as you can revert a document you are editing to a known good version. This allows you to more robustly have a reproducible output from the VM.

- Manageability: the VM is software, so can be saved and restored as you might a document file (albeit a much larger file than a typical document!).

- Migration: the VM is just data, so a complete VM can be transmitted to another physical host and run in the same way from there.

- Shareability: If you want to share your computational setup with someone else, you can transmit the VM to another person and they can run it on their host - you do not need to send them your actual computer!

Types of virtualisation:

- Full (hardware-level) virtualisation (software): Full virtualisation uses software that recreates the hardware environment of a hardware platform within which virtual machines can be run. A virtual machine sees the environment provided by the virtualisation software as the hardware it is running on, and the virtualisation software, in turn, makes use of the physical hardware of the host system to provide the actual computational resources to run the virtual machine. In standard virtualisation, the virtualisation software provides an environment that is the same as or similar to the host system. However, there is no reason why it can’t present a platform that looks, to the software running on it, like a completely different type of hardware - this is known as emulation - the virtualisation software is emulating another type of system.

- Full (hardware-level) virtualisation (hardware): Complete virtualisation of a hardware platform implemented entirely in software can be very resource intensive. Traditionally, a virtual machine running in virtualisation software on your host could be expected to run certain tasks significantly slower than if they were running directly on the host system’s hardware. In recent years, hardware support for virtualisation has been introduced into x86 processors to help improve the speed of virtualisation which has become increasingly widely used with the emergence of cloud platforms and large-scale multi-core hardware.

- Shared-kernel (operating system-level) virtualisation: This is a higher-level approach to virtualisation that has traditionally been most commonly seen on Unix variants such as Linux (e.g. OpenVZ) and Solaris (e.g. Solaris Zones). This is the same approach used by modern container platforms such as Docker and Singularity. “Virtual machines” or “containers” share the running kernel of the host operating system which makes things more lightweight and potentially offers better performance. A downside of this approach is that it is only possible to run operating systems compatible with the kernel of the host system in a shared-kernel/container environment. The virtual environment operates within a segregated area of the host system, seeing only its own filesystem and other hardware resources to which it has been allowed access. While this doesn’t provide the same level of isolation as a fully virtualised environment, the rapid development of container tools and platforms and their increasingly wide use means that rapid progress is being made in this area.

Downsides of virtualisation:

- The file describing a VM has to contain its entire simulated hard-disk, so this leads to very large files.

- The guest computer wastes a lot of time managing “hardware” that’s not actually real, e.g., VMs need to boot up in the same way that your laptop does.

- A host needs lots of RAM to run large numbers of virtual machines, as the strong isolation means that the VMs do not share any resources.

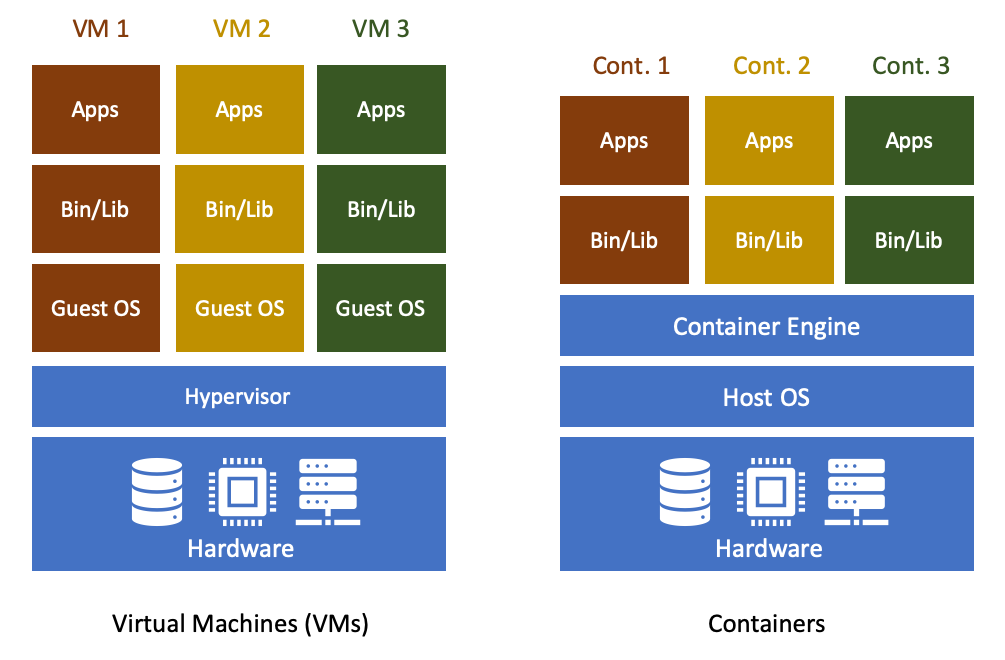

Containers are a type of lightweight virtualisation

Containers are similar to full, hardware-level virtual machines but offer a more lightweight solution. As highlighted above, containers sacrifice the strong isolation that full virtualisation provides in order to vastly reduce the resource requirements on the virtualisation host.

The term “container” can be usefully considered with reference to shipping containers. Before shipping containers were developed, packing and unpacking cargo ships was time consuming, and error prone, with high potential for different clients’ goods to become mixed up. Similar to VMs, software containers standardise the packaging of a complete software system (the lightweight virtual machine): you can drop a container into a container host, and it should “just work”.

On this course, we will be using Linux containers - all of the containers we will meet are based on the Linux operating system in one form or another. However, the same Linux containers we create can run on:

- macOS;

- Microsoft Windows;

- Linux; and

- The Cloud

We should certainly see people using the same containers on macOS and Windows today.

And what do you do?

Think about your work. How does computing help you do your research? How do you think containers (or virtualisation) could help you do more or better research?

Write a few sentences on this topic in the supplied online whiteboard in the section about yourself that you created earlier.

Containers and file systems

One complication with using a virtual environment such as a container (or a VM) is that the file systems (i.e. the directories that the container sees) can now potentially come from two different locations:

- Internal file systems: these provide directories that are part of the container itself and are not visible on the host outside the container. These directories can have the same location as directories on the host but the container will see its internal version of the directories rather than the host versions.

- Host file systems: these are directories mapped from the host into the container to allow the container to access data on the host system. Some container systems (e.g. Singularity) map particular directories into the container by default while others (e.g. Docker) do not generally do this. Note that the location (or path) to the directories in the container is not necessarily the same as that in the host. The command you use to start the container will usually provide a way to map host directories to directories in the container.

This is illustrated in the diagram below:

Host system: Container:

------------ ----------

/ /

├── bin ├── bin <-- Overrides host version

├── etc ├── etc <-- Overrides host version

├── home ├── usr <-- Overrides host version

│ └── auser/data ───> mapped to /data in container ──> ─┐ ├── sbin <-- Overrides host version

├── usr │ ├── var <-- Overrides host version

├── sbin └───────├── data

└── ... └── ...

Although there are many use cases for containers that do not require mapping host directories into the container, a lot of real-world use cases for containers in research do use this feature and we will see it in action throughout this lesson.

Docker and Singularity

Even though we will focus on Singularity during this course, it is worth highlighting Docker.

Docker is software that manages containers and the resources that containers need. While Docker is a leader in the container space, there are many similar technologies available and the concepts we learn today will allow us to use other container platforms even if their command syntax will be a little different.

SingularityCE or Apptainer are widely available on shared high performance computing systems where Docker’s design makes is unsuitable for the multi-user nature of these systems.

SingularityCE or Apptainer

Singularity started a project but in 2021 the project split into two versions, Sylabs continued via SingularityCE whilst Linux Foundation hosted Apptainer. Currently similar in features but could diverge as priorities differ for each project.

Terminology

Before we start the course, we will introduce some of the technical terms:

- Image: this is the term that describes the template for the virtual hard disk contents (files and folders) from which live instances of containers will be created. The term “container image” may sometimes be used to emphasise that the “image” relates to software containers and not, say, the sense of an “image” when discussing VMs or cute kitten pictures (without loss of generality).

- If you are interested in more technical details, Docker actually creates images by combining together multiple layers, although you can profitably use Docker without knowing much about layers. As a quick summary, each layer is a given set of files and folders. The combination of layers essentially involves a set-wise union of the files and folders in the layers, except that there is also a way for upper layers to hide files from lower layers (which has the appearance of deleting those files). Layers facilitate efficient storage space use, by allowing container images to share and reuse sets of files and folders, while still allowing individual container images to have their own specific files and folders.

- Container: this is an instance of a lightweight virtual machine created from a (container) image.

- Docker Hub: the Docker Hub is a storage resource and associated website where a vast collection of preexisting container images are documented and stored, and are made available for your use.

Key Points

Almost all software depends on other software components to function, but these components have independent evolutionary paths.

Projects involving many software components can rapidly run into a combinatorial explosion in the number of software version configurations available, yet only a subset of possible configurations actually works as desired.

Virtualisation is an approach that can collect software components together and can help avoid software dependency problems.

Containers are a popular type of lightweight virtualisation that are widely used.

Docker and Singularity are two different software platforms that can create and manage containers and the resources they use.